Musing 89: Adapting While Learning: Grounding LLMs for Scientific Problems with Intelligent Tool Usage Adaptation

Interesting paper out of Tsinghua and UC San Diego

Today’s paper: Adapting While Learning: Grounding LLMs for Scientific Problems with Intelligent Tool Usage Adaptation. Lyu et al. 1 Nov. 2024. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.00412

LLMs demonstrate promising capabilities in solving simple scientific problems but often produce hallucinations for complex ones. Compared to direct reasoning alone, using scientific tools such as physics-based simulators enables the handling of more complex problem-solving tasks without incurring hallucinations. Following this trajectory, integrating LLMs with such specialized tools represents a natural evolution to improve their problem-solving capabilities. Unfortunately, when trained solely on tool usage, LLMs tend to over-rely on tools, even for problems solvable through basic reasoning. This not only increases computational costs due to resource-intensive scientific tools but also limits the model’s ability to internalize knowledge.

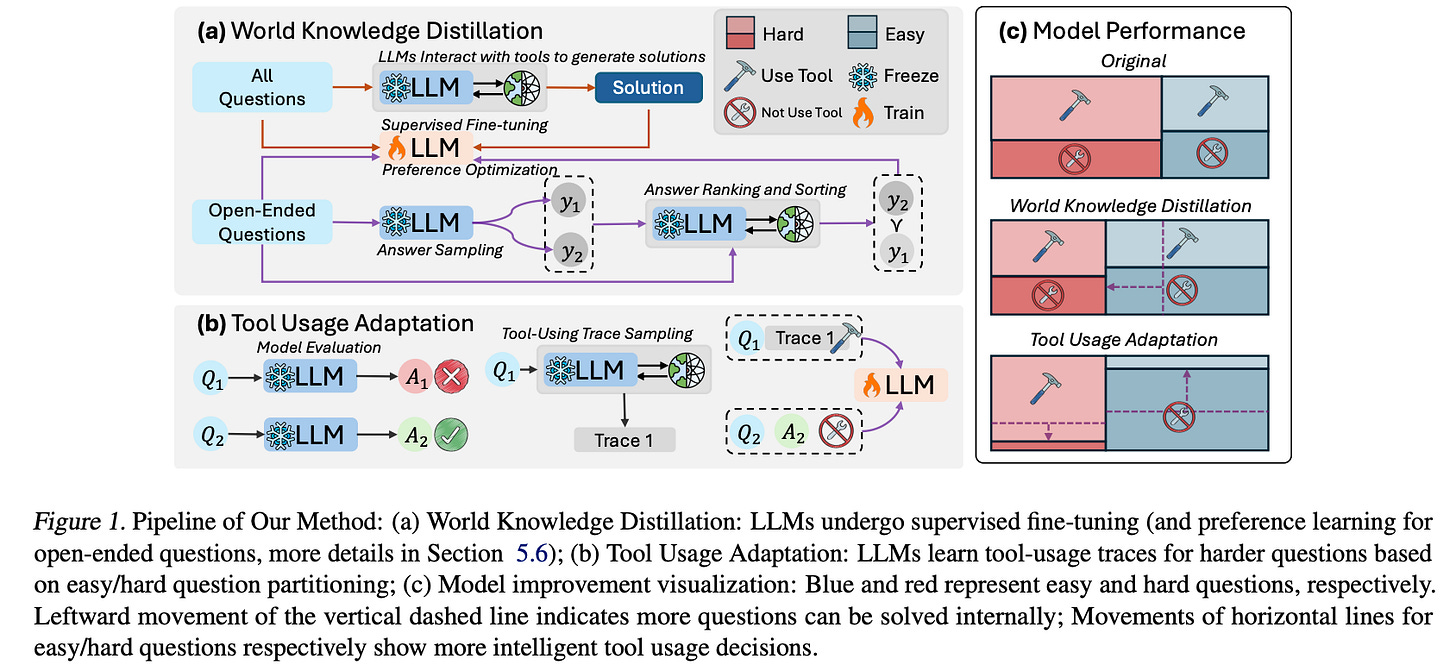

In today’s paper, the authors consider a solution to this problem by proposing a novel training paradigm consisting of two components. The first component, World Knowledge Distillation (WKD), uses supervised fine-tuning and preference learning to align a pre-trained LLM with highly accurate solutions generated using information from external tools, aiming to internalize scientific knowledge. In the second component, Tool Usage Adaptation (TUA), they evaluate the LLM’s direct answering ability and classify questions as easy or hard based on the model’s accuracy. While maintaining the same alignment target for easy questions, they train the model to follow external tool traces for hard questions, enabling intelligent switching based on problem complexity. Figure 1 below illustrates their fine-tuning pipeline and its intended target.

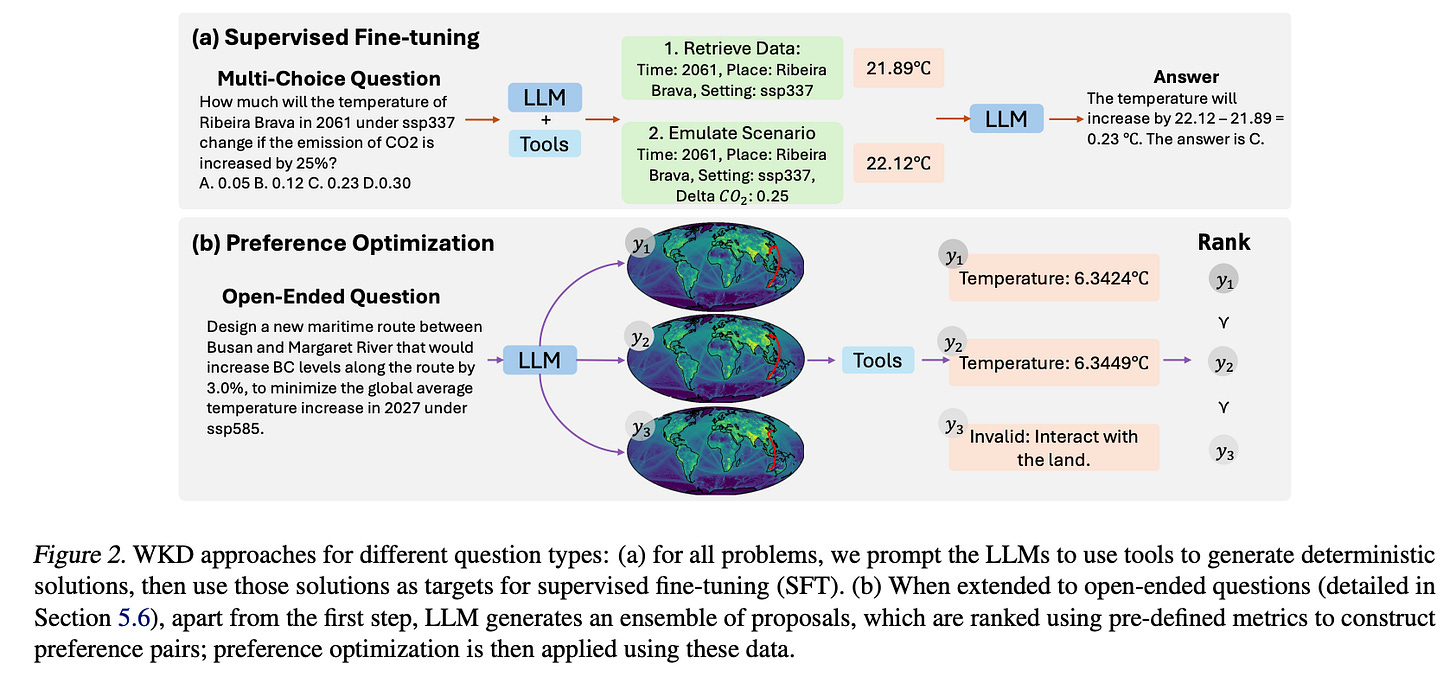

The approach draws inspiration from human expert behavior. The authors observe that experts first assess a scientific problem’s complexity before deciding whether to employ basic reasoning or specialized tools. They aim to instill similar adaptive capabilities in LLMs through these two components. Figure 2 below demonstrates the solution generation pipeline and its application to both multiple-choice and open-ended questions. It shows two main examples: multiple-choice and open-ended questions. For multiple-choice questions, the LLM uses tools to gather exact values or perform calculations that enable it to choose the correct answer. For open-ended questions, the LLM generates an ensemble of possible answers, which are ranked using predefined metrics. This allows the model to learn from more complex problem-solving scenarios, adjusting its answers based on the structured data provided by tools.

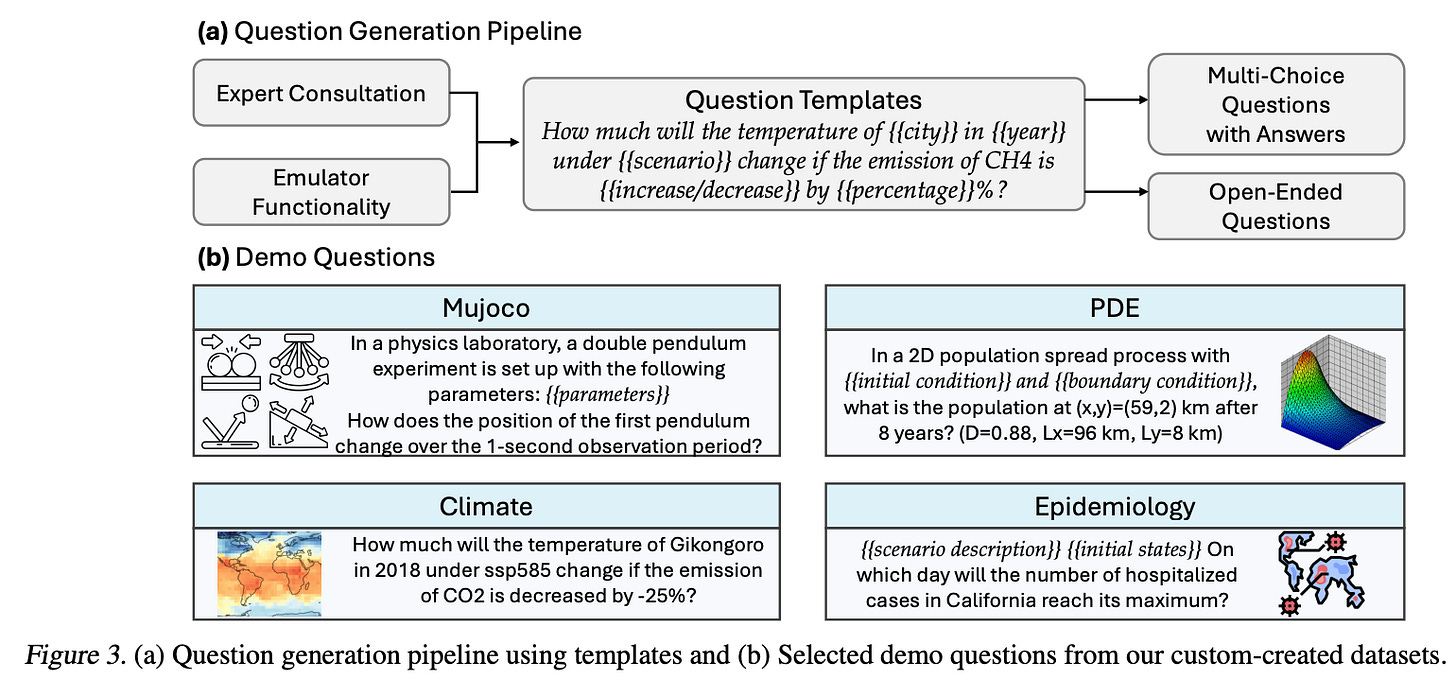

Figure 3 provides further details on the question generation pipeline and examples of demo questions from various scientific domains. 3a illustrates the systematic pipeline used to create questions tailored to scientific domains like climate science, epidemiology, and physics simulations. It starts with expert consultation and tool functionality to design questions that are scientifically rigorous. The pipeline uses templates for questions, which help structure queries with parameters relevant to each domain. These templates guide the types of questions generated, such as specific scenarios (e.g., emission levels, climate scenarios) in climate science or detailed settings for experiments in physics or epidemiology.

3b presents examples of questions produced by the pipeline for different domains. For instance, it shows physics-related queries about a double pendulum's motion, climate science questions about temperature predictions under different emissions scenarios, and epidemiological inquiries about the spread of disease. These questions vary in structure, including both multiple-choice and open-ended formats, depending on the domain and the tools used to generate solutions.

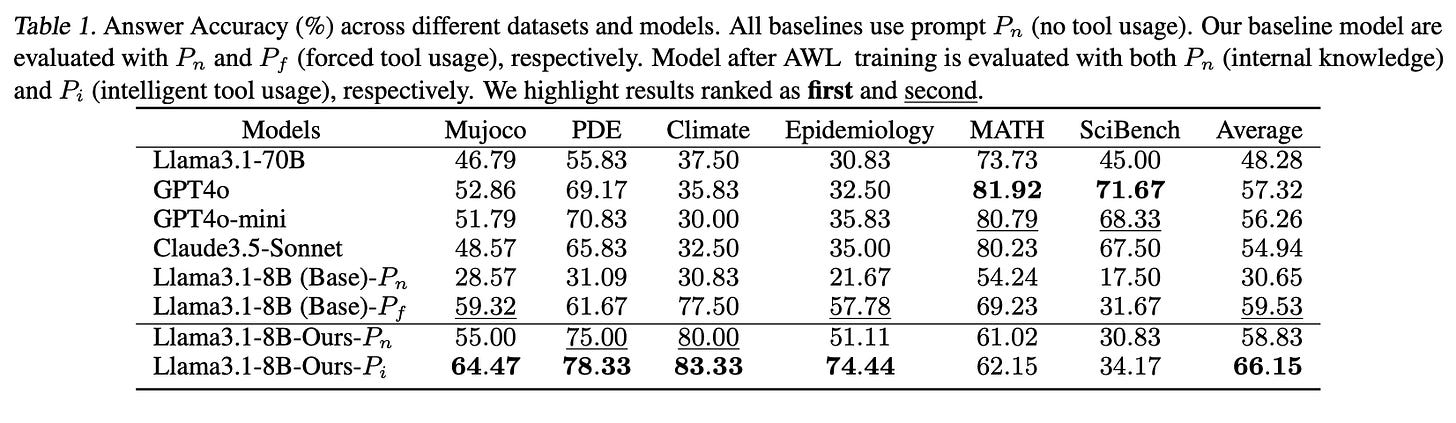

On to experiments. The authors employ two existing public datasets, MATH and SciBench, and also construct four new scientific datasets for the experiments: Mujoco, Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), Climate Science, and Epidemiology. They use Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct as the base model for their training scheme. They also conducted extensive evaluations of other state-of-the-art (SOTA) open and closed-source models, including GPT4o, GPT4o-mini, Claude-3.5-Sonnet, and Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct. For measuring performance, two types of accuracy were computed: Answer Accuracy and Tool Usage Accuracy.

Answer accuracy quantifies the proportion of correct answers provided by the models. For multiple-choice questions (MCQs) in the custom-created datasets, the authors assign binary scores based on whether the model selects the correct choice. For numerical answers in the MATH and SciBench datasets, they consider answers correct if they fall within a small tolerance range of the true value, specifically within ±5%. Tool usage accuracy assesses whether the model can make intelligent decisions regarding tool usage, i.e., using tools for difficult questions while answering directly for easier ones. Questions are partitioned into Easy (E) or Hard (H) based on whether they are answerable by a trained model with P_n (no tool usage). When using P_i , which allows tool choice, the decisions are further labeled with T (tool used) or N (no tool used). They then used a formula to compute the accuracy.

Table 1 below presents the answer accuracy of various models across different datasets, highlighting how effectively the proposed model performs on scientific problems across multiple domains. The model trained with the authors’ method ("Llama3.1-8B-Ours-Pi") achieves the highest average answer accuracy across all datasets at 66.15%, significantly outperforming both the baseline models and other prompting configurations.

The custom-trained model performs particularly well on the newly developed datasets (Mujoco, PDE, Climate, Epidemiology), which involve complex scientific questions that the LLM has not encountered before. For instance:

On the Climate dataset, "Llama3.1-8B-Ours-Pi" achieves an accuracy of 83.33%, the highest among all models, indicating its strong ability to adapt to climate science questions.

Similarly, it reaches 74.44% accuracy on the Epidemiology dataset, surpassing other models by a considerable margin.

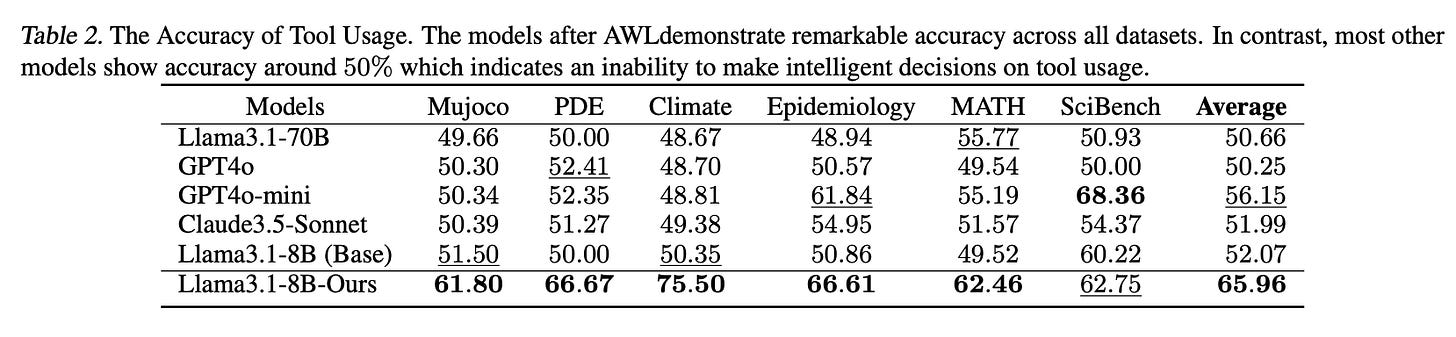

Table 2 below shows the Tool Usage Accuracy. On specific datasets like Mujoco and Climate, "Llama3.1-8B-Ours" performs exceptionally well, achieving 61.80% and 75.50% tool usage accuracy, respectively. This demonstrates the model’s adaptability in deciding when to leverage tools effectively in fields like physics (Mujoco) and climate science. In contrast, other models (such as GPT4o and Claude3.5-Sonnet) generally score close to 50% across datasets, which indicates they either over-rely on tools or rarely use them, failing to adaptively toggle tool usage based on question difficulty.

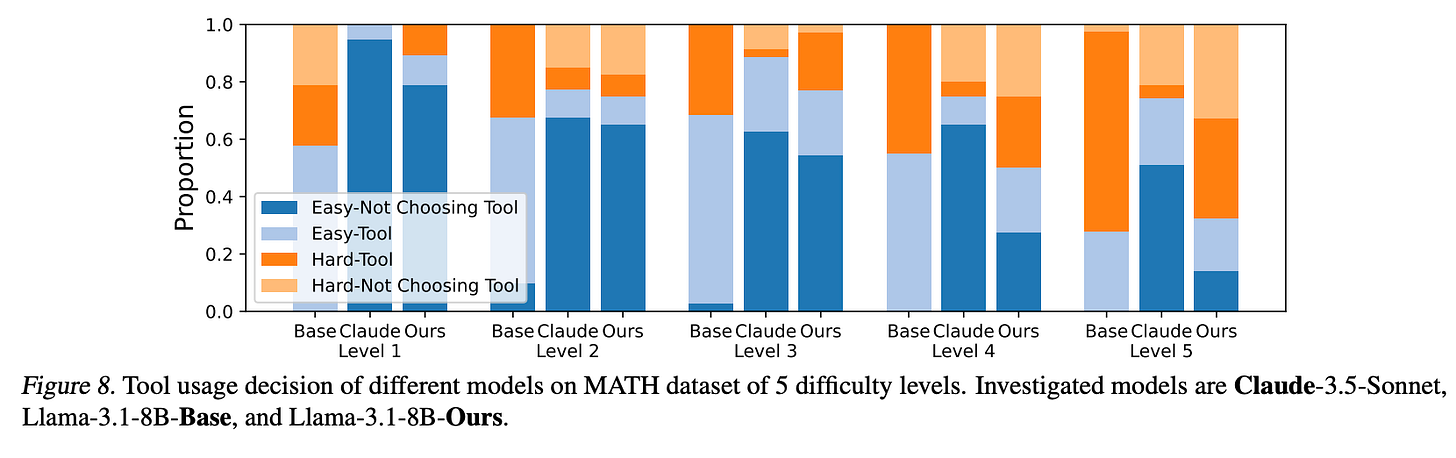

Supplementing the results, Figure 8 below illustrates tool usage decisions across five difficulty levels of the MATH dataset, comparing three models: Claude-3.5-Sonnet, Llama-3.1-8B-Base, and Llama-3.1-8B-Ours (the model trained with the authors' WKD and TUA methods). The figure divides tool usage decisions into four categories:

Easy-Not Choosing Tool (EN): Easy questions where the model correctly chose not to use a tool.

Easy-Tool (ET): Easy questions where the model unnecessarily chose to use a tool.

Hard-Tool (HT): Hard questions where the model correctly chose to use a tool.

Hard-Not Choosing Tool (HN): Hard questions where the model incorrectly chose not to use a tool.

Some key insights:

The "Llama-3.1-8B-Ours" model, trained with WKD and TUA, shows a clear increase in tool usage as the difficulty level rises. This demonstrates that the model effectively adapts its tool usage based on question difficulty.

The baseline "Llama-3.1-8B-Base" model, which lacks the adaptive training methods, demonstrates an over-reliance on tools, even for easier questions. The figure shows a high proportion of ET decisions across all levels, suggesting it lacks the ability to judge when tool usage is unnecessary, leading to inefficient and sometimes irrelevant tool calls.

In contrast, the "Claude-3.5-Sonnet" model displays a tendency to avoid tool usage even on hard questions, with a high proportion of HN decisions, especially at higher difficulty levels. This indicates the model’s confidence in its direct answering capabilities, possibly due to previous exposure to similar questions during training. However, this approach leads to errors on harder questions where tool usage would have improved accuracy.

Concluding this musing, it seems the experimental performance is quite strong. The results highlight that the "Llama3.1-8B-Ours" model trained with the authors’ approach (combining WKD and TUA) can better discern when tools are needed. By avoiding unnecessary tool usage on simpler questions, the model conserves computational resources and improves response efficiency. The approach could serve as a paradigm and foundation for creating reliable AI scientific assistants, and the authors note several promising directions for future investigation: their current approach requires domain-specific fine-tuning, future research could explore methods for unifying cross-domain training in related scientific fields. Incorporating step-wise adaptive tool utilization, i.e., adaptive decision-making on tool usage at each step, could significantly reduce human preprocessing workload. Finally, expanding the method to handle multi-modal inputs and outputs would broaden its applicability to settings where data extends beyond textual formats.